By: Edgar Bustamante

1. Introduction

In the first section, I will refer to the regional developments and historical data about telecommunications infrastructure in Latin America. Secondly, I will establish the background of telecommunications in Latin America and the Caribbean, and the political and economic transformations that developed in the region during those years. I will also mention the historical conflicts that major telecommunication projects have suffered because of the instability in the region. Where it is usual to find tight regulation and sometimes even contradictory sentences from local courts that tend to complicate business relationships in Latin America. Further, I will refer to the risk of dealing with third world government authorities, which has been a long time enemy of international investment. In this sense, governments established preference for corruption while rejecting the possibility to lessen the gap of technology access. A conduct that has subjected many economies to cuantious reparations arising out of failed public-private projects.

Eventually, this reality slowed down the pace of latin telecommunication development, notwithstanding the great opportunities for investments in infrastructure for regional networks that existed throughout the 20th century. Nevertheless, a few of those opportunities did become major projects reflected in joint ventures and private investments which transformed networks and connectivity points across the continent, a situation that brought together fellow countries in the south of the continent.

Furthermore, I will mention the positive aspects that propelled telecommunications in the region, and will also address the projects that faced a wide variety of issues that lead them to gargantuan arbitration proceedings. Some of them which transcended as landmark cases that will be referenced to understand the complexity of public-private joint ventures and failed associations in the region.

The third point will focus on the general attitude that governments in the region demonstrated throughout the last decades in Latin America, specifically towards telecommunications projects that relied on arbitration, BIT’s and PPT’s.

Finally, the fourth point will determine if the acceptance and adoption of the practice of international arbitration had a positive or negative impact in the development of the telecommunications sector.

2. Sector

The telecommunications sector in Latin America has been subjected to a great deal of technological change and in some areas the growth has been spectacular. In this region, the traditional fixed-line telephone service has not grown nearly as fast as the mobile service. Indeed, the mobile service is a substitute for it, although the fixed-line does offer the opportunity to provide an Internet or even broadband internet services. Even in developing countries, individuals are “cutting-the-chords” and giving up their fixed-line in favor of cellular service.

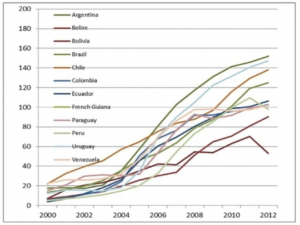

According to data from The International Telecommunication Union shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, the cellular telephone service has skyrocketed in Latin America in the last two decades, where virtually all countries have 100 percent or better penetration. Several, much better, such as: Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay, which have over 1.2 cellular phones for every inhabitant.

Figure 1. Mobiles per 100 inhabitants, Latin America

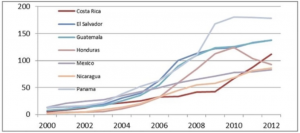

Similarly, Central America and Mexico (see Figure 2) have also seen spectacular growth in wireless. Whereas Panama has the lead in Central America with 1.8 wireless phones for every one inhabitant. Most of the other countries are above or near one mobile per person, where Honduras, Mexico and Nicaragua are the stragglers with slightly under 100 mobile phones per 100 inhabitants.

Figure 2. Mobiles per 100 inhabitants, Central America and Mexico

To update the aforementioned data, it is relevant to state that the smartphone penetration per capita in Latin America was 7.6 percent in 2011. In 2017, the smartphone penetration per capita is projected to reach 39.1 percent.[1]

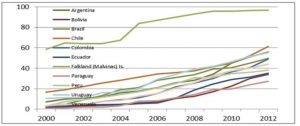

Regarding internet services, we can verify that the pattern for penetration has not been as dramatic as wireless-mobile service. Nevertheless, it has made significant progress over the last dozen years of growth, especially in Chile, Uruguay and Argentina.

Figure 3. Internet per 100 inhabitants, Latin America

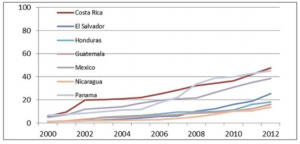

Figure 4. Internet per 100 inhabitants, Central America & Mexico[2]

In 1975, most of the Latin American nations broke free of the protectionist policies arising out of the Calvo Doctrine and adopted the Panama Convention, which favored arbitration and foreign investment. Nevertheless, the effect of the Convention varied by country and by court, where some procedural laws faced unprecedented efforts to enforce arbitral awards in many cases.[3]

Hence, the region continued to face considerable issues and impediments in spite of the major growth related to the aforementioned services during the last two decades. More so, the discipline of arbitration required a certain standard for legal stability in many countries with imprevisible political changes. These factors were essential for the efficacy of arbitral practice, but they were not always on display. Thus, one should take into consideration the back and forth transitions from dictatorship to democracy, prodded by norms and regimes or international law.[4]Because of this, different clashes of models in the region arose. Some of them were propelled by joint ventures between public and private partnerships while some were left to the mercy of government authorities. Thus, some of the risks we can identify are:

- Delay the introduction of new services and infrastructure;

- Block or reduce the flow of capital from investors;

- Limit competition, leading to higher pricing and lower service quality; and

- Retard liberalization, and with it, general economic, social and technical development.

Another issue that discouraged technological growth Latin America was the harsh nature of negotiations with governmental authorities. Where the interactions between public and private entities, and sometimes mixed public and private companies, were subject to a high political sensitivity and publicity. One ought to know that, when state parties get involved it is usually to undermine the importance of ICSID arbitration and the many arbitration proceedings initiated by foreign private investors against host countries. Where parties such as Brazil and Argentina, produced a great number of disputes, specially against spanish and italian corporations such as Telefonica and Telecom.

Naturally, the sector has many subsectors and a wide variety of reasons for disputes to arise in relation to telecommunications, for example:

- Intellectual Property claims;

- IT implementation programs;

- Data related issues;

- Reputation management issues;

- Outsourcing programs.

We have to understand that obtaining information at a large scale seems pretty demanding since there is a high number of arbitration clauses inserted into telecommunications related contracts in the region. In spite of that, it is safe to say that there is a constant and widespread use of this type of clauses in all types of telecommunications related transactions, such sectors include: telecommunicatoin equipment, fixed-line, cellular, undersea cable, long distance, phone card and public phone subsectors.

Another related aspect to the development of telecommunications in the region has been the introduction and standardization of business models such as the Public Private Partnerships (“PPT’s”). Where there is usually a dispute resolution provision included in every variation of this contract that binds it to international arbitration proceedings or to a neutral foreign jurisdiction elected by the parties.

Further, PPT’s allowed foreign investors to adhere to different Bilateral Agreements between countries which typically include:

- A right to a fair and equitable treatment, usually understood to include the investors’ legitimate expectations;

- The obligation on the host state not to depart from any commitments or undertakings entered into with foreign investors;

- The obligation not to adopt arbitrary or unreasonable measures;

- The obligation not to impair qualifying investments and

- The protection against direct or indirect expropriation.

Furthermore, historical data suggests that existing regulatory and legal institutions are not always well equipped to either identify or resolve disputes efficiently and effectively. Therefore, policymakers, regulators and courts, are adopting a range of alternative approaches to dispute resolution that protect investments and PPT’s.

When facing the aforementioned risks, private parties who sat down for negotiations with government officials needed to reinforce the security of their investment. Naturally, they started to apply arbitration clauses in their contracts to seek for transparent proceedings in case of disputes with the state. This trend resulted in a huge investment opportunity in the region since it was possible for investors to identify possible risks and conflicts in early stages. Therefore, they were more likely to engage in negotiations with countries with underdeveloped infrastructure in the telecommunication sector. This was particularly crucial for countries that have historically experienced a lack of investment and growth. A situation that changed thanks to a rapid and effective resolution of disputes, which was a key component in bridging this “digital divide.”

We have to consider that most arbitration proceedings in telecommunication projects require specific provisions that amount to a certain standard of security when investing. For example, strong confidentiality provisions and flexibility to appoint experts are the most required in this sense. The first one is generally utilized to protect high-end patent technology that could drive the trend in mobile products in a given year, for example, or even position a new provider over a traditional one because of new and highly developed access to connectivity in a specific territory. In a general way, the advantages of arbitration include:

- Choice of arbitrators;

- Specialization of the arbitrators;

- Arbitrators are empowered to grant interim relief;

- Possibility to adopt fast track proceedings (a tool when dealing with the ever-changing technological sphere);

- Choice of the applicable law;

- Choice of the arbitration venue;

- Choice of the language;

- Limited grounds for appeal;

- Efficient mechanism for enforcing the award (New-York Convention of 1958);

- Contrary to that, we could argue that one of the main disadvantages is that confidentiality is not fully protected under some institutional rules, such as the ICC Rules.

Nevertheless, telecommunications regulators are increasingly encouraging parties to use arbitration as a way to resolve disputes. There are numerous, well-established arbitration institutions around the world that have developed their own procedures and trained arbitrators. So, if any given country lacks resources in this sense, they are often able to find them somewhere else in their region. Arbitration forums include the AAA,[5] ICC, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), local chambers or arbitration tribunals and National Regulatory Agency (NRAs).

Now, regarding landmark cases in the region, it is important to recall Elettronica Industriale S.P.A. v. Venezolana de Televisión, C.A. (VTV). In this case, the parties got into an arbitration proceeding after an alleged breach of a concession agreement. Where the Supreme Court of Venezuela set aside an arbitral award for non-conformity of the arbitration agreement with the then recently enacted Venezuelan Commercial Arbitration Act.

The main reasons were that, according to the Supreme Court, the arbitral agreement had not been authorized by the Ministry of the Secretariat of the Presidency; that neither the President nor the Board of Directors of VTV had the capacity to execute the arbitral agreement; and that the subject matter of the dispute was not capable of settlement by arbitration, being a “Contrato de Interes Publico Nacional” (public interest contract).

This sort of decision confirmed the bias against private investors in Latin American jurisdictions with complex legal culture like Venezuela. This decision was surprising because the contract was executed before the enactment of the Venezuelan Commercial Arbitration Act; the documentation provided seemed to confirm that the officers involved did had the power to enter into arbitration agreements; and finally, it is known that international arbitration proceedings are permitted in public interest contracts with commercial nature in Venezuela.

Thus, government intrusion against arbitration tends to confirm certain biases that foreign investors hold against the region. This is particularly true in the energy sector, where abrupt increases in oil and gas prices put tremendous political pressure on local governments to recuperate allegedly “excess” revenues from foreign investors. This was the case of Ecuador v. Oxy, where a buy-out agreement was sought by Oxy with another private entity to participate in the petroleum blocks in Ecuador. An action that, according to Ecuador, violated both the Participation Contract and Ecuadorian law, which required ministerial approval.

Other government intrusion examples can be found in Argentina and Brazil. For example, in the Yacyretá case in Argentina, the courts granted an injunction ordering the suspension of the ICC arbitral process until the terms of reference were reviewed by the competent court. A decision that was based on an obiter dictum in the Cartellone case which states that there is always the possibility of resorting to national courts if the arbitrator’s decision is “unconstitutional, illegal or unreasonable.”

In Brazil, it can be said that two principles apply in determining whether a dispute with a state or state-owned company can be arbitrated, according to Brazilian law. The first is the “principle of legality” set forth in Article 37 of the Brazilian Constitution, according to which public assets and rights are always subject to prior legislative authorization. The second principle is one of arbitrability, which provides that the government could agree to arbitrate only with respect to so-called “disposable assets”.

This shows that there is in fact an attempt to reconcile arbitration proceedings with local law in the region. Nevertheless, government actions tend to tightly scrutinize or delay a process because of the public impact it may exert in the public eye. Further, there have been several arbitration claims directed to recalculate profits and tariffs due under concession agreements. A lot of them were even admitted by the national courts, which is generally not a good trend for the progress of arbitration in the region.

Finally, the appearance of arbitration legislation in complex jurisdictions such as Ecuador have shifted private expectations in the right way. A perfect example is the newly enacted “Ley de Modernización y Atracción de Inversiones,” a law that seeks to attract foreign investment by establishing de facto arbitration for public works and recognition of foreign arbitral awards. Features that were already adopted for many years by players such as Perú, Colombia and Chile. This scenario is truly groundbreaking for upcoming and long-time participants in the sector, who may enjoy a firmer ground to fight instability and corruption in latin american government.

3. Discussion

According to the information presented, it is safe to say that the telecommunication sector shifted between different scenarios but was ultimately supported by different tools such as the newly adapted arbitration culture, PPT ventures and positive local laws for arbitration.

Further, it is important to state that some Supreme Courts did authorize arbitration proceedings for major projects between the State and private investors, such as the case of Brazil and Panama, who were asked to recognize both domestic and foreign arbitral awards in telecommunication cases.

On the other hand there are exceptions like Ecuador and Venezuela, who have denounced the ICSID Convention and have demonstrated adversity towards arbitration institutions. More so, these states have claimed on more than one occasion that the “public good” was a primordial asset for them, even to justify unilateral termination of incompleted public infrastructure projects that have cost millions of dollars to the average taxpayer. An unprecedented blow to an internationally renowned arbitration institution by then dictators Rafael Correa and Hugo Chavez.

4. Implications

It is still not completely clear whether the legal systems of Latin American states have the means or the will to execute the two main judicial responsibilities of international arbitration: compelling arbitral proceedings and enforcing awards.[6] As it was previously stated, the cases vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Nevertheless, arbitration became widely accepted in the Latin American business community and permitted considerable economic integration.[7] This succeeded because foreign investors saw an opportunity to engage in a sector who already had technology available for general application, but was just sitting there waiting for the opportunity to join the Latin American landscape. Because of this, vast opportunities developed throughout the region and primary networks and connectivity grids were up to date with the rest of the world, functioning and serving a complex nation like it is Latin America.

Footnotes:

[1] Smartphone user penetration as percentage of total population in Latin America from 2011 to 2018, Statista, (Aug. 28, 2014), https://www.statista.com/statistics/203719/smartphone-penetration-per-capita-in-latin-america-since-2006/.

[2] James Alleman & Paul Rappoport, Regulation Of Latin American’s Information & Communications Technology (Ict) Sector: An Empirical Analysis, Institut Barcelona Estudis Internacionals Working Papers 9–12 (2015), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep14193?seq=12#metadata_info_tab_contents (last visited Apr 2, 2020).

[3] Gary Born, International Commercial Arbitration in the United States: Commentary and Materials (1st ed. 1994).

[4] Harold Hongju Koh, Transnational Legal Process, Yale Law School (1996), https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/2096/ (last visited Apr 2, 2020).

[5] Jonathan C. Hamilton, Three Decades of Latin American Arbitration, 30 U. Pa. J. Int’l L. 1099 (2009).

[6] Paul Stephan & Julie Roin, International Business and Economics Document Supplement: Law and Policy (4th ed. 2010).

[7] Id. at 202.